Articles

Features

Articles

Safety

Safety News

Recognition of electrical injury remains an uphill battle

April 22, 2022 | By Anthony Capkun

Dr. Marc Jeschke on the state of research and treatment

April 22, 2022 – Frustratingly, non-visible electrical injury—that is, where there are no apparent wounds and burns—continues to be largely misunderstood, questioned, and even ignored by the medical community, healthcare providers and insurance companies, employers and co-workers.

The subject of electrical injury—and the research being done at St. John’s Rehab and Ross Tilley Burn Centre in Toronto—have had a special place in my heart ever since my visit to St. John’s Rehab for our special feature “The Road to Recovery from Invisible Electrical Injury” back in 2010 (below).

Back then, when we interviewed Dr. Joel Fish (then chief medical officer for St. John’s Rehab) about non-visible electrical injury, he said: “I myself in the beginning didn’t believe this existed”.

Have attitudes changed at all?

A dozen years have gone by since then. Outside of obvious electrical injury, like a burn, have attitudes changed at all with regard to non-visible electrical injury?

“Frustratingly, I would say not a lot,” said Dr. Marc Jeschke who, among numerous other positions and credentials, is the current director of the Ross Tilley Burn Centre, part of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. “To this day, people struggle to get accepted and to be recognized to have had an electrical injury.”

His experience with electrical injury stems back to his time with the Shriners’ hospital for children at Galveston (UTMB, University of Texas Medical Branch), where he saw a significant amount of paediatric patients—as well as adults—from Mexico or Central America being admitted with electrical injuries… typically caused by tapping into live powerlines.

He agrees with Fish’s statement, admitting electrical injury was a learning curve for him as well, before realizing “Wow, there is a significant impact of an injury that is not being recognized because you don’t have testing”.

“So, unfortunately, despite lots of talks, papers—and there are numerous out there published by various people, indicating the impact of low-voltage, non-visible electrical burns—we still don’t have recognition,” Jeschke says. “That is very frustrating for patients, but also for care providers, because we don’t get the resources to treat them. And this is very sad.”

Jeschke is now familiar with the symptoms of electrical injury. “I don’t need to know anything about the patient. When I hear symptoms like: ‘I can’t focus. I can’t sleep. I can’t concentrate. I have headaches. I feel fatigued, I feel exhausted,’ I know 100% this is an electrical injury.”

Digestion problems may be present, as well as muscle pain, muscle agony, or seizures. More severe cases may seem like a stroke had occurred, where the patient can’t move or walk. There are neurologic deficits, Jeschke explains.

And it would be frustrating because, as Jeschke says, the general opinion would be “Well, it must be all in your mind”.

“I always tell my patients: I’m sorry you have to go through this nightmare [of testing], but it will all be negative… so don’t get frustrated.”

“So I think that is very frustrating for patients,” he admits, especially if the patient is being followed by a private investigator (i.e. from an insurance company), “because [they think] it’s all made up”.

It’s not surprising, then, that the existence of non-visible, low-voltage injury is not quite accepted by medical professionals as a thing, let alone by insurance agencies, employers—even fellow employees.

The toll on mental health

Private investigators. Suffering from an injury that few, if any, acknowledge. That has to take a toll on someone’s mental health! Jeschke believes this aspect of the injury is completely under-appreciated.

One study published in the British Medical Journal found that the mental health of 50% of patients was affected, Jeschke notes. “Anxiety, depression… you name it, there are major mental health alterations. Regardless whether it’s high voltage or low voltage, you can have a very strong impact.”

“So you can imagine that you have these symptoms, then nobody takes you seriously… I mean, it’s not a surprise that people can get extremely depressed or anxious,” he says.

And with the lack of proper diagnostics, Jeschke wonders: Are these patients truly depressed, or is there some other medical explanation for what looks like depression?

“It would be nice to have this understood better. And that is what we’re doing. We’re actually looking into electrically injured patients to see what exactly is on the axis of depression and mental health? What are we really dealing with, and how can we treat it?”

Research is the key to progress

Perhaps a decade is too brief a period to see significant advancement in what could be considered a rare injury. That said, surely some progress has been made?

“There are several things we learned over the last 10 years. First is the impact low-voltage electrical injuries can have,” says Jeschke, who goes on to explain that—while they still haven’t unravelled the mystery—they are working toward understanding how electricity affects the cell membrane and various cellular components; and something called channelopathies, where your cell channels are being affected.

“And I’m very confident that, by the next five to 10 years, we will have a better understanding.”

“I think it is very important to develop new therapies, but what we’re missing is diagnostics,” he says. “We know all the testing will be negative and, when you have negative testing, the injury must be all in your mind, so it doesn’t exist,” Jeschke bemoans. “You run EMGs, EEGs, MRIs, CTs—you name it—we do all the testing and we don’t find anything.”

Breakthroughs, however small, are being made. Jeschke says he has presented on this subject to Ontario’s WSIB (Workplace Safety & Insurance Board), and he believes their understanding and acceptance is “something that has improved” over the last 10 years.

Diagnostics. Therapies. None of that happens without continued research, and you can’t do a lot of that without funding. Unfortunately, funding is hard to come by because—in the grand scheme of things—electrical injury (and burns, for that matter) is relatively rare, which is why it is “not heavily of interest for funding agencies, because it doesn’t impact the broad masses”.

“To actually achieve anything, and to move forward and to have some diagnostics, you need donations. Donations and support from the industry are highly appreciated and needed—otherwise, you can’t conduct research.”

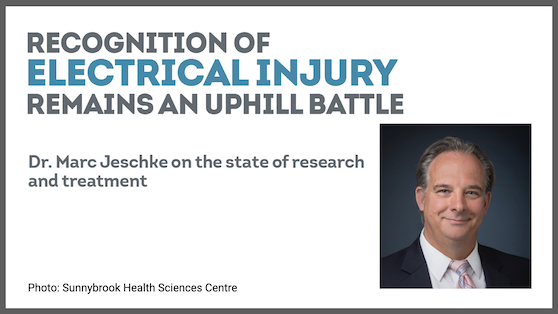

Dr. Jeschke is very excited about a hand-held 3D “skin printer” that he is developing in collaboration with U of T Engineering to cover large burn wounds. The printer’s “bio ink” accelerates the healing process using the patient’s own cells. (Left to Prof. Axel Guenther and Ph.D. candidate Richard Cheng with the 3D skin printer. Photo: Daria Perevezentsev, courtesy University of Toronto Engineering.

The Ross Tilley Burn Centre and St. John’s Rehab have embarked on a joint program in electrical injury care and research to ensure the highest possible quality of care is available to patients with electrical injuries.

But their work is far from complete. Specialized treatments for unique injuries advance only when industry rallies to support that research, so I strongly encourage everyone in the electrical sector to do what they can to help fund Ross Tilley Burn Centre and St. John’s Rehab’s program in electrical injury care.

To make a gift that will support Sunnybrook’s research into electrical burn injuries, call 416-480-4833 or visit sunnybrook.ca/donate.

Ultimately, the goal with continued research is to achieve a greater understanding that leads to successful treatments for sufferers. Being able to diagnose the electrical injury—and not have all those tests come back negative—would go a long way toward making non-visible electrical injury visible.

Also watch our interview with Dr. Jeschke (below):

You’ll find all our Back Issues in the Digital Archive.

Print this page