Features

Energy & Power

Transmission & Distribution

Scale-up renewables generation to match the scale of weather systems

January 26, 2016 | By Anthony Capkun

January 25, 2016 – Because the sun is shining or winds are blowing across the United States all of the time somewhere, a new study by NOAA and University of Colorado Boulder researchers shows the States could slash greenhouse gas emissions from power production by up to 78% below 1990 levels within 15 years—even while meeting increased demand.

Their study used a mathematical model to evaluate future cost, demand, generation and transmission scenarios. It found that, with improvements in transmission infrastructure, weather-driven renewable resources could supply most of the nation’s electricity at costs similar to today’s.

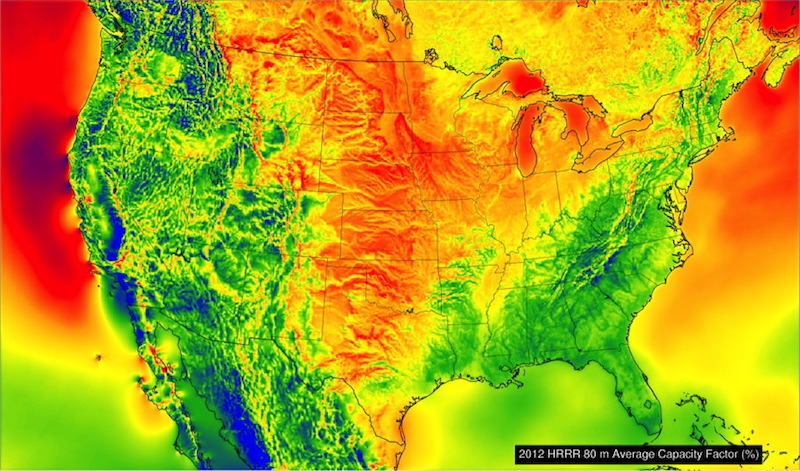

PHOTO: A high-resolution map based on NOAA weather data showing wind energy potential across the United States in 2012. Image by Chris Clack/CIRES.

“Our research shows a transition to a reliable, low-carbon, electrical generation and transmission system can be accomplished with commercially available technology and within 15 years,” said Alexander MacDonald, co-lead author and recently retired director of NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) in Boulder.

While improvements in wind and solar generation continue to drive down the cost of producing renewable energy, these energy resources are inherently intermittent. As a result, utilities have invested in surplus generation capacity to backup renewable energy generation with natural gas-fired generators and other reserves.

“In the future, they may not need to,” said co-lead author Christopher Clack, a physicist and mathematician at CU-Boulder.

MacDonald theorized that the key to resolving the dilemma of intermittent renewable generation might be to scale-up the renewable energy generation system to match the scale of weather systems. So he assembled a team of four other NOAA scientists to explore the idea.

Using NOAA’s high-resolution meteorological data, they built a model to evaluate the cost of integrating different sources of electricity into a national energy system. The model estimates renewable resource potential, energy demand, CO2 emissions and the costs of expanding and operating electricity generation and transmission systems to meet future needs.

The model allowed researchers to evaluate the affordability, reliability and GHG emissions of various energy mixes, including coal. It showed that low-cost and low-emissions are not mutually exclusive.

“The model relentlessly seeks the lowest-cost energy, whatever constraints are applied,” Clack said. “And it always installs more renewable energy on the grid than exists today.”

Even in a scenario where renewable energy costs more than experts predict, the model produced a system that cuts CO2 emissions 33% below 1990 levels by 2030, and delivered electricity at about $0.086/kWh. By comparison, electricity cost $0.094/kWh in 2012.

Were renewable energy costs lower and natural gas costs higher, the modelled system sliced CO2 emissions by 78% from 1990 levels and delivered electricity at $0.10/kWh. (The year 1990 is a standard scientific benchmark for greenhouse gas analysis, says CU-Boulder.)

A scenario that included coal yielded lower cost ($0.085/kWh) but, not surprisingly, the highest emissions.

This new paper, the researchers say, suggests the U.S. could cut total CO2 emissions 31% below 2005 levels by 2030 by making changes only within the electric sector, even though the electrical sector represents just 38% of the national CO2 budget. These changes would include rapidly expanding renewable energy generation and improving transmission infrastructure.

In identifying low-cost solutions, researchers enabled the model to build and pay for transmission infrastructure improvements—specifically, a new, high-voltage DC (HVDC) grid to supplement the current electrical grid. Their model did “choose to use [HVDC] lines extensively”, and the study found that investing in efficient, long-distance transmission was key to keeping costs low.

MacDonald compared the idea of a HVDC grid with the interstate highway system from the 1950s. “With an ‘interstate for electrons’, renewable energy could be delivered anywhere in the country while emissions plummet,” he said. “An HVDC grid would create a national electricity market in which all types of generation—including low-carbon sources—compete on a cost basis. The surprise was how dominant wind and solar could be.”

“It shows that intermittent renewables plus transmission can eliminate most fossil-fuel electricity while matching power demand at lower cost than a fossil fuel-based grid—even before [energy] storage is considered,” said Stanford University’s Mark Jacobson.

Print this page